Drive north from Winnemucca on a two-lane highway for about ninety miles and you’ll reach a stretch of high desert that most Nevadans have never heard of. Thacker Pass doesn’t have much going on at first glance—sagebrush, jackrabbits, the occasional pronghorn silhouette against the Montana Mountains. But beneath this quiet landscape lies a deposit that has geologists, mining executives, environmentalists, and tribal nations locked in one of the most consequential land-use fights in the American West.

Lithium Americas Corp. wants to build an open-pit mine here that would become the largest lithium mine in the United States. The company says the project is essential for the clean-energy transition—lithium is the key ingredient in the batteries that power electric vehicles, and domestic supply is almost nonexistent. Opponents say the mine would drain an already stressed aquifer, destroy thousands of acres of old-growth sagebrush habitat, and desecrate land that Indigenous communities consider sacred.

Both sides have a point. And that’s exactly what makes Thacker Pass worth paying attention to.

What’s Actually in the Ground

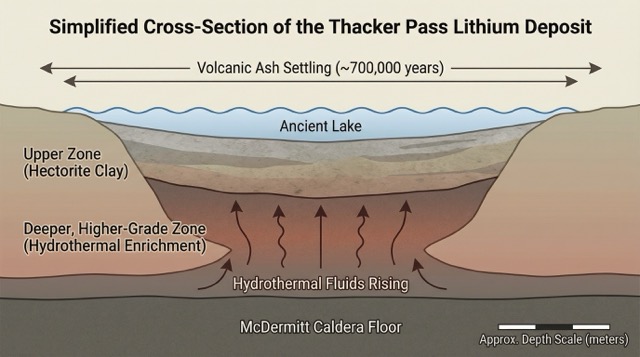

The deposit sits at the southern edge of the McDermitt Caldera, a massive volcanic structure roughly 45 km by 30 km that straddles the Nevada–Oregon border. The caldera formed about 16.4 million years ago when a supervolcano erupted and collapsed—part of the same geologic system that eventually produced Yellowstone. After the collapse, a lake filled the basin for roughly 700,000 years. Volcanic ash drifted into that lake and settled into layers of fine-grained claystone, some of it more than 200 meters thick.

Over millions of years, two things happened to that claystone that made it extraordinary. First, ordinary groundwater chemistry altered the volcanic glass into lithium-bearing clay minerals, mainly a type called hectorite. That alone would make a decent deposit. But then a second wave of heat-driven fluids—pushed upward by renewed magmatic activity beneath the caldera floor—supercharged the deepest layers, converting hectorite into a much richer mineral called tainiolite-like illite, with lithium concentrations two to three times higher than anything found in comparable deposits worldwide. A 2020 study by Castor and Henry in the journal Minerals described this dual enrichment process in detail.

In practical terms, the numbers are staggering. The 2022 feasibility study estimated proven and probable reserves of roughly 3.7 million tonnes of lithium carbonate equivalent—enough to supply batteries for hundreds of thousands of electric vehicles per year for decades. Phase 1 alone targets 40,000 tonnes of annual lithium carbonate production.

The Water Problem

Here’s where it gets complicated. The mine plan calls for an open pit reaching 300 to 400 feet below the surface, which means cutting through the regional water table. At full capacity, operations would consume about 1.7 billion gallons of groundwater per year from the Quinn River Valley aquifer. That’s a basin the Nevada Division of Water Resources has already flagged as over-appropriated—meaning more water rights have been issued than the aquifer can sustainably provide. In a region that gets less than 10 inches of rain a year, that’s a serious concern.

It’s not just about volume. The claystone itself contains disseminated pyrite, plus elevated levels of antimony, arsenic, and uranium. When you dig up pyrite-bearing rock and expose it to air and rainwater, you get sulfuric acid—the textbook mechanism behind acid mine drainage. The Bureau of Land Management’s Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) acknowledges this risk but relies on engineered liner systems in the tailings storage facility to prevent contaminants from reaching groundwater. Independent peer review of those containment models has been limited.

Downstream of the project area, Thacker Creek supports populations of Lahontan cutthroat trout (listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act) and endemic Kings River pyrg springsnails. The Nevada Department of Wildlife has stated on the record that the mine would cause adverse impacts to wildlife, surface and groundwater, and riparian vegetation. Some opponents warn that antimony mobilized from disturbed rock could persist in the shallow aquifer for centuries.

Sacred Ground, Rushed Timelines

The environmental concerns alone would make this a contentious project. But Thacker Pass carries another layer of significance. The Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe, the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony, and the Winnemucca Indian Colony consider this area culturally and spiritually important. In the Paiute language, the site is known as Peehee mu’huh—roughly translated as “rotten moon.” Historical accounts suggest that a U.S. cavalry massacre of Paiute people may have taken place here in 1865. Tribal representatives have argued that the federal consultation process failed to meet the standard of free, prior, and informed consent.

The permitting timeline has also raised eyebrows. The BLM completed its entire environmental review in under twelve months and issued the Record of Decision on January 15, 2021—five days before a new presidential administration took office. For a project of this scale, that pace is unusual; comparable mine reviews typically stretch across multiple years. Environmental groups and a local rancher filed lawsuits within weeks of the approval, and legal challenges have continued since.

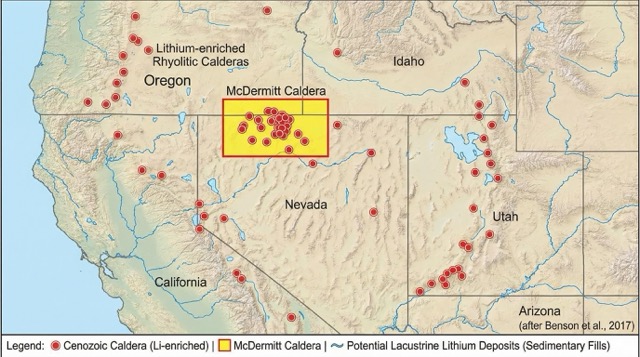

Not Just Thacker Pass

It’s tempting to see this as a one-off fight over one mine in one corner of Nevada. But it’s not. A 2017 study published in Nature Communications by Benson and colleagues at Stanford and the USGS identified more than 100 calderas across the western United States and northern Mexico with the geochemical signatures of lithium-enriched magmas. Several contain lake-sediment fills similar to McDermitt’s. As lithium demand grows—the International Energy Agency projects a 40-fold increase in lithium demand by 2040 under a net-zero scenario—exploration pressure on these sites will only intensify.

The precedents being set at Thacker Pass right now—how fast environmental reviews move, how much baseline hydrologic data is considered sufficient, how Indigenous concerns factor into the process—will ripple across the next generation of domestic lithium projects.

The Balance

Nobody serious about climate change disputes that we need lithium. The math on decarbonizing transportation doesn’t work without it, and relying entirely on foreign supply chains carries its own risks. But there’s a difference between acknowledging that lithium mining is necessary and accepting that any particular mine, at any particular site, under any particular timeline, is beyond question.

At Thacker Pass, the geology is remarkable—a genuine scientific curiosity produced by an ancient supervolcano meeting an ancient lake. The resource is real and significant. But so are the aquifer drawdown projections, the acid-generating potential of the host rock, the threatened trout downstream, and the cultural weight this land carries for the people who have lived alongside it for thousands of years.

The clean-energy transition needs lithium. It also needs public trust. Cutting corners on the science to speed up the supply chain is a good way to lose both.

• • •

Further Reading & Sources

Castor, S.B., and Henry, C.D. (2020). “Lithium-Rich Claystone in the McDermitt Caldera, Nevada, USA.” Minerals, 10(1), 68. Read the paper →

Benson, T.R., et al. (2017). “Lithium enrichment in intracontinental rhyolite magmas leads to Li deposits in caldera basins.” Nature Communications, 8, 270. Read the paper →

Benson, T.R., Mahood, G.A., and Grove, M. (2017). “Geology and geochronology of the middle Miocene McDermitt volcanic field.” GSA Bulletin, 129(9–10), 1027–1051. Read the paper →

Bureau of Land Management (2020). Thacker Pass Lithium Mine Project — Final Environmental Impact Statement. View the FEIS →

U.S. Department of Energy — Thacker Pass Project Overview. View on energy.gov →

Nevada Division of Environmental Protection — Thacker Pass Project Page. View on NDEP →

About the Author

Suzanne Militello is an exploration geologist based in Reno, Nevada, with fieldwork experience across the Great Basin. Her work focuses on the intersection of mineral resource assessment and environmental geochemistry. She conducted independent field observations at Thacker Pass between 2019 and 2021.